Daylight saving time (DST), also referred to as daylight saving(s), daylight savings time, daylight time (United States and Canada), or summer time (United Kingdom, European Union, and others), is the practice of advancing clocks to make better use of the longer daylight available during summer so that darkness falls at a later clock time. The typical implementation of DST is to set clocks forward by one hour in spring or late winter, and to set clocks back by one hour to standard time in the autumn (or fall in North American English, hence the mnemonic: “spring forward and fall back”).

As of 2025, polls indicate a majority of those polled in the United States favor abolishing DST,[1] with momentum gaining in all areas where the practice persists to either abolish DST and switch permanently to standard time,[2] or make DST permanent. Some of the most commonly cited reasons for abolishing DST or making it permanent include the numerous health risks as well as the economic costs imposed by the changing of clocks, lost sleep, and disruptions to daily routines for millions of people.[3]

Overview

[edit]

As of 2023, around 34 percent of the world’s countries use DST.[4] Some countries observe it only in some regions. In Canada, all of Yukon, most of Saskatchewan, and parts of Nunavut, Ontario, British Columbia and Quebec do not observe DST. It is observed by four Australian states and one territory. In the United States, it is observed by all states except Hawaii and Arizona (within the latter, however, the Navajo Nation does observe it).[5]

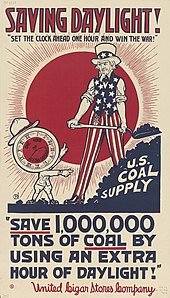

Historically, several ancient societies adopted seasonal changes to their timekeeping to make better use of daylight; Roman timekeeping even included changes to water clocks to accommodate this. However, these were changes to the time divisions of the day rather than setting the whole clock forward. In a satirical letter to the editor of the Journal de Paris in 1784, Benjamin Franklin suggested that if Parisians could only wake up earlier in the summer they would economize on candle and oil usage, but he did not propose changing the clocks.[6][7] In 1895, New Zealand entomologist and astronomer George Hudson made the first realistic proposal to change clocks by two hours every spring to the Wellington Philosophical Society, but this was not implemented until 1928 and in another form.[8] In 1907, William Willett proposed the adoption of British Summer Time as a way to save energy; although seriously considered by Parliament, it was not implemented until 1916.[9]

The first implementation of DST was by Port Arthur (today merged into Thunder Bay), in Ontario, Canada, in 1908, but only locally, not nationally.[10][11] The first nation-wide implementations were by the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires, both starting on 30 April 1916. Since then, many countries have adopted DST at various times, particularly since the 1970s energy crisis.

Rationale

[edit]

Industrialized societies usually follow a clock-based schedule for daily activities that do not change throughout the course of the year. The time of day that individuals begin and end work or school, and the coordination of mass transit, for example, usually remain constant year-round. In contrast, an agrarian society‘s daily routines for work and personal conduct are more likely governed by the length of daylight hours[12][13] and by solar time, which change seasonally because of the Earth’s axial tilt. North and south of the tropics, daylight lasts longer in that hemisphere’s summer and is shorter in that hemisphere’s winter, with the effect becoming greater the farther one moves away from the equator. DST is of little use for locations near the Equator, because these regions see only a small variation in daylight over the course of the year.

After synchronously resetting all clocks in a region to one hour ahead of standard time in spring in anticipation of longer daylight hours, individuals following a clock-based schedule will be awakened an hour earlier in the solar day than they would have otherwise. They will begin and complete daily work routines an hour earlier; in most cases, they will have an extra hour of daylight available to them after their workday activities.[14][15]

The clock shift is partly motivated by practicality. At the summer solstice, in American temperate latitudes, for example, the sun rises around 4:30 standard time and sets around 19:30. Since most people are asleep at 04:30, it is seen as practical to treat 04:30 as if it were 05:30, thereby allowing people to wake closer to the sunrise and be active in the evening light, as the sun under DST sets an hour later (20:30). The longer evening daylight hours are attractive to golfers, for example, while farmers traditionally expressed dislike for having to be out working while dew is still heavy.

Proponents of daylight saving time argue that most people prefer more daylight hours after the typical “nine to five” workday.[16][17] Supporters have also argued that DST decreases energy consumption by reducing the need for lighting and heating, but the actual effect on overall energy use is heavily disputed.[18][19] For evaluation, it is required to go beyond considering only energy demand for lighting and also consider the energy used for heating or cooling buildings.[20]

Variation within a time zone

[edit]

The effect of daylight saving time also varies according to how far east or west the location is within its time zone, with locations farther east inside the time zone benefiting more from DST than locations farther west in the same time zone.[21] Despite a width spanning thousands of kilometers, all of China is located within a single time zone per government mandate, increasing the daylight shift the farther west one is.

History

[edit]

Ancient civilizations adjusted daily schedules to the sun more flexibly than DST does, often dividing daylight into 12 hours regardless of daytime, so that each daylight hour became progressively longer during spring and shorter during autumn.[22] For example, the Romans kept time with water clocks that had different scales for different months of the year; at Rome’s latitude, the third hour from sunrise (hora tertia) started at 09:02 solar time and lasted 44 minutes at the winter solstice, but at the summer solstice it started at 06:58 and lasted 75 minutes.[23] From the 14th century onward, equal-length civil hours supplanted unequal ones, so civil time no longer varied by season. Unequal hours are still used in a few traditional settings, such as monasteries of Mount Athos[24] and in Jewish ceremonies.[25]

Benjamin Franklin published the proverb “early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise”,[26][27] and published a letter in the Journal de Paris when he was an American envoy to France (1776–1785) suggesting that Parisians economize on candles by rising earlier to use morning sunlight.[28] This 1784 satire proposed taxing window shutters, rationing candles, and waking the public by ringing church bells and firing cannons at sunrise.[29] Despite common misconception, Franklin did not actually propose DST; 18th-century Europe did not even keep precise schedules. However, this changed as rail transport and communication networks required a standardization of clocks unknown in Franklin’s day.[30]

In 1810, the Spanish National Assembly Cortes of Cádiz issued a regulation that moved certain meeting times forward by one hour from 1 May to 30 September in recognition of seasonal changes, but it did not change the clocks. It also acknowledged that private businesses were in the practice of changing their opening hours to suit daylight conditions, but they did so of their volition.[31][32]

New Zealand entomologist George Hudson first proposed modern DST. His shift-work job gave him spare time to collect insects and led him to value after-hours daylight.[8] In 1895, he presented a paper to the Wellington Philosophical Society proposing a two-hour daylight-saving shift,[14] and considerable interest was expressed in Christchurch; he followed up with an 1898 paper.[33] Many publications credit the DST proposal to prominent English builder and outdoorsman William Willett,[34] who independently conceived DST in 1907 during a pre-breakfast ride when he observed how many Londoners slept through a large part of a summer day.[17] Willett also was an avid golfer who disliked cutting short his round at dusk.[35] His solution was to advance the clock during the summer, and he published the proposal two years later.[36] Liberal Party member of parliament Robert Pearce took up the proposal, introducing the first Daylight Saving Bill to the British House of Commons on 12 February 1908.[37] A select committee was set up to examine the issue, but Pearce’s bill did not become law and several other bills failed in the following years.[9] Willett lobbied for the proposal in the UK until his death in 1915.

Port Arthur, Ontario, Canada, was the first city in the world to enact DST, on 1 July 1908.[10][11] This was followed by Orillia, Ontario, introduced by William Sword Frost while mayor from 1911 to 1912.[38] The first states to adopt DST (German: Sommerzeit) nationally were those of the German Empire and its World War I ally Austria-Hungary commencing on 30 April 1916, as a way to conserve coal during wartime. Britain, most of its allies, and many European neutrals soon followed. Russia and a few other countries waited until the next year, and the United States adopted daylight saving in 1918. Most jurisdictions abandoned DST in the years after the war ended in 1918, with exceptions including Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Ireland, and the United States.[39] It became common during World War II (some countries adopted double summer time), and was standardized in the US by federal law in 1966, and widely adopted in Europe from the 1970s as a result of the 1970s energy crisis. Since then, the world has seen many enactments, adjustments, and repeals.[40]

It is a common myth in the United States that DST was first implemented for the benefit of farmers.[41][42][43] In reality, farmers have been one of the strongest lobbying groups against DST since it was first implemented.[41][42][43] The factors that influence farming schedules, such as morning dew and dairy cattle‘s readiness to be milked, are ultimately dictated by the sun, so the clock change introduces unnecessary challenges.[41][43][44]

DST was first implemented in the US with the Standard Time Act of 1918, a wartime measure for seven months during World War I in the interest of adding more daylight hours to conserve energy resources.[45][44] Year-round DST, or “War Time“, was implemented again during World War II.[45] After the war, local jurisdictions were free to choose if and when to observe DST until the Uniform Time Act which standardized DST in 1966.[45][46] Permanent daylight saving time was enacted for the winter of 1974, but there were complaints of children going to school in the dark and working people commuting and starting their work day in pitch darkness during the winter, and it was repealed a year later.[citation needed]

Procedure

[edit]

See also: Daylight saving time by country

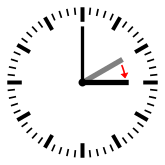

When DST observation begins, clocks are advanced by one hour during the very early morning.

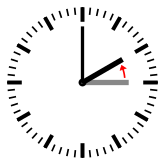

When DST observation ends and standard time observation resumes, clocks are turned back one hour during the very early morning.

Specific times of the clock change vary by jurisdiction.

The relevant authorities usually schedule clock changes to occur at (or soon after) midnight and on a weekend, in order to lessen disruption to weekday schedules.[47] A one-hour change is usual, but twenty-minute and two-hour changes have been used in the past. Notable exceptions today include Lord Howe Island with a thirty-minute change, and Troll (research station) that shifts two hours directly between CEST and GMT since 2016.[48] In all countries that observe daylight saving time seasonally (i.e., during summer and not winter), the clock is advanced from standard time to daylight saving time in the spring, and it is turned back from daylight saving time to standard time in the autumn.

For a midnight change in spring, a digital display of local time would appear to jump from 23:59:59.9 to 01:00:00.0. For the same clock in autumn, the local time would appear to repeat the hour preceding midnight, i.e. it would jump from 23:59:59.9 to 23:00:00.0.

In most countries that observe seasonal daylight saving time, clocks revert in winter to standard time.[49][50] An exception exists in Ireland, where its winter clock has the same offset (UTC+00:00) and legal name as that in Britain (Greenwich Mean Time)—but while its summer clock also has the same offset as Britain’s (UTC+01:00), its legal name is confusingly called Irish Standard Time[51][52] as opposed to British Summer Time.[53]

Since 2019, Morocco observes daylight saving time every month but Ramadan. During the holy month (the date of which is determined by the lunar calendar and thus moves annually with regard to the Gregorian calendar), the country’s civil clocks observe Western European Time (UTC+00:00, which geographically overlaps most of the nation). At the close of that month, its clocks are turned forward to Western European Summer Time (UTC+01:00).[54][55][56]

The time at which to change clocks differs across jurisdictions. Members of the European Union conduct a coordinated change, changing all zones at the same instant, at 01:00 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), which means that it changes at 02:00 Central European Time (CET), equivalent to 03:00 Eastern European Time (EET). As a result, the time differences across European time zones remain constant.[57][58] North America coordination of the clock change differs, in that each jurisdiction changes at each local clock’s 02:00, which temporarily creates an imbalance with the next time zone (until it adjusts its clock, one hour later, at 2 am there). For example, Mountain Time is for one hour in the spring two hours ahead of Pacific Time instead of the usual one hour ahead, and instead of one hour in the autumn, briefly zero hours ahead of Pacific Time.

The dates on which clocks change vary with location and year; consequently, the time differences between regions also vary throughout the year. For example, Paris (which uses Central European Time) is usually six hours ahead of New York City (which uses North American Eastern Time), except for a few weeks in March and October/November when it is five hours ahead. Paris and Santiago are six hours apart during the northern summer, four hours during the southern summer, and five hours for a few weeks per year. Since 1996, European Summer Time has been observed from the last Sunday in March to the last Sunday in October; previously the rules were not uniform across the European Union.[58] Starting in 2007, most of the United States and Canada observed DST from the second Sunday in March to the first Sunday in November, almost two-thirds of the year.[59] Moreover, the beginning and ending dates are roughly reversed between the northern and southern hemispheres because spring and autumn are displaced six months. For example, mainland Chile observes DST from the second Saturday in October to the second Saturday in March, with transitions at the local clock’s 24:00.[60] In some countries, clocks are governed by regional jurisdictions within the country such that some jurisdictions change and others do not; this is currently the case in Australia, Canada, and the United States.[61][62]

From year to year, the dates on which to change clock may also move for political or social reasons. The Uniform Time Act of 1966 formalized the United States’ period of daylight saving time observation as lasting six months (it was previously declared locally); this period was extended to seven months in 1986, and then to eight months in 2005.[63][64][65] The 2005 extension was motivated in part by lobbyists from the candy industry, seeking to increase profits by including Halloween (31 October) within the daylight saving time period.[66] In recent history, Australian state jurisdictions not only changed at different local times but sometimes on different dates. For example, in 2008 most states there that observed daylight saving time changed clocks forward on 5 October, but Western Australia changed on 26 October.[67]

Politics, religion and sport

[edit]

The concept of daylight saving has caused controversy since its early proposals.[68] Winston Churchill argued that it enlarges “the opportunities for the pursuit of health and happiness among the millions of people who live in this country”[69] and pundits have dubbed it “Daylight Slaving Time”.[70] Retailing, sports, and tourism interests have historically favored daylight saving, while agricultural and evening-entertainment interests (and some religious groups[71][72][73][74]) have opposed it; energy crises and war prompted its initial adoption.[75]

Willett’s 1907 proposal illustrates several political issues. It attracted many supporters, including Arthur Balfour, Churchill, David Lloyd George, Ramsay MacDonald, King Edward VII (who used half-hour DST or “Sandringham time” at Sandringham), the managing director of Harrods, and the manager of the National Bank Ltd.[76] However, the opposition proved stronger, including Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, William Christie (the Astronomer Royal), George Darwin, Napier Shaw (director of the Meteorological Office), many agricultural organizations, and theatre-owners. After many hearings, a parliamentary committee vote narrowly rejected the proposal in 1909. Willett’s allies introduced similar bills every year from 1911 through 1914, to no avail.[77] People in the US demonstrated even more skepticism; Andrew Peters introduced a DST bill to the House of Representatives in May 1909, but it soon died in committee.[78]

Germany and its allies led the way in introducing DST during World War I on 30 April 1916, aiming to alleviate hardships due to wartime coal shortages and air-raid blackouts. The political equation changed in other countries; the United Kingdom used DST first on 21 May 1916.[79] US retailing and manufacturing interests—led by Pittsburgh industrialist Robert Garland—soon began lobbying for DST, but railroads opposed the idea. The US’ 1917 entry into the war overcame objections, and DST started in 1918.[80]

The end of World War I brought a change in DST use. Farmers continued to dislike DST, and many countries repealed it—like Germany itself, which dropped DST from 1919 to 1939 and from 1950 to 1979.[81] Britain proved an exception; it retained DST nationwide but adjusted transition dates over the years for several reasons, including special rules during the 1920s and 1930s to avoid clock shifts on Easter mornings. As of 2009, summer time began annually on the last Sunday in March under a European Community directive, which may be Easter Sunday (as in 2016).[58] In the US, Congress repealed DST after 1919. President Woodrow Wilson—an avid golfer like Willett—vetoed the repeal twice, but his second veto was overridden.[82] Only a few US cities retained DST locally,[83] including New York (so that its financial exchanges could maintain an hour of arbitrage trading with London), and Chicago and Cleveland (to keep pace with New York).[84] Wilson’s successor as president, Warren G. Harding, opposed DST as a “deception”, reasoning that people should instead get up and go to work earlier in the summer. He ordered District of Columbia federal employees to start work at 8 am rather than 9 am during the summer of 1922. Some businesses followed suit, though many others did not; the experiment was not repeated.[15]

Since Germany’s adoption of DST in 1916, the world has seen many enactments, adjustments, and repeals of DST, with similar politics involved.[85] The history of time in the United States features DST during both world wars, but no standardization of peacetime DST until 1966.[86][87] St. Paul and Minneapolis, Minnesota, kept different clocks for two weeks in May 1965: the capital city decided to switch to daylight saving time, while Minneapolis opted to follow the later date set by state law.[88][89] In the mid-1980s, Clorox and 7-Eleven provided the primary funding for the Daylight Saving Time Coalition behind the 1987 extension to US DST. Both senators from Idaho, Larry Craig and Mike Crapo, voted for it based on the premise that fast-food restaurants sell more French fries (made from Idaho potatoes) during DST.[90]

A referendum on the introduction of daylight saving took place in Queensland, Australia, in 1992, after a three-year trial of daylight saving. It was defeated with a 54.5% “no” vote, with regional and rural areas strongly opposed, and those in the metropolitan southeast in favor.[91]

In 2003, the United Kingdom’s Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents supported a proposal to observe year-round daylight saving time, but it has been opposed by some industries, by some postal workers and farmers, and particularly by those living in the northern regions of the UK.[13]

In 2005, the Sporting Goods Manufacturers Association and the National Association of Convenience Stores successfully lobbied for the 2007 extension to US DST.[92]

In December 2008, the Daylight Saving for South East Queensland (DS4SEQ) political party was officially registered in Queensland, advocating the implementation of a dual-time-zone arrangement for daylight saving in South East Queensland, while the rest of the state maintained standard time.[93] DS4SEQ contested the March 2009 Queensland state election with 32 candidates and received one percent of the statewide primary vote, equating to around 2.5% across the 32 electorates contested.[94] After a three-year trial, more than 55% of Western Australians voted against DST in 2009, with rural areas strongly opposed.[95] Queensland Independent member Peter Wellington introduced the Daylight Saving for South East Queensland Referendum Bill 2010 into the Queensland parliament on 14 April 2010, after being approached by the DS4SEQ political party, calling for a referendum at the next state election on the introduction of daylight saving into South East Queensland under a dual-time-zone arrangement.[96] The Queensland parliament rejected Wellington’s bill on 15 June 2011.[97]

Russia declared in 2011 that it would stay in DST all year long (UTC+4:00) and Belarus followed with a similar declaration.[98] (The Soviet Union had operated under permanent “summer time” from 1930 to at least 1982.) Russia’s plan generated widespread complaints due to the dark of winter-time mornings, and thus was abandoned in 2014.[99] The country changed its clocks to standard time (UTC+3:00) on 26 October 2014, intending to stay there permanently.[100]

In the United States, Arizona (with the exception of the Navajo Nation), Hawaii, and the five populated territories (American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the US Virgin Islands) do not participate in daylight saving time.[101][102] Indiana only began participating in daylight saving time as recently as 2006. Since 2018, Florida Republican Senator Marco Rubio has repeatedly filed bills to extend daylight saving time permanently into winter, without success.[103]

Mexico observed summertime daylight saving time starting in 1996. In late 2022, the nation’s clocks “fell back” for the last time, in restoration of permanent standard time.[104]

Religion

[edit]

Some religious groups and individuals have opposed DST on religious grounds. For religious Muslims and Jews it makes religious practices such as prayer and fasting more difficult or inconvenient.[105][72][73][74] Some Muslim countries, such as Morocco, have temporarily abandoned DST during Ramadan.[74]

In Israel, DST has been a point of contention between the religious and secular, resulting in fluctuations over the years, and a shorter DST period than in the EU and US. Religious Jews prefer a shorter DST[a] due to DST delaying scheduled morning prayers, thus conflicting with standard working and business hours. Additionally, DST is ended before Yom Kippur (a 25-hour fast day starting and ending at sunset, much of which is spent praying in synagogue until the fast ends at sunset) since DST would result in the day ending later, which many feel makes it more difficult.[b][72][106]

In the US, Orthodox Jewish groups have opposed extensions to DST,[107] as well as a 2022 bipartisan bill that would make DST permanent, saying it will “interfere with the ability of members of our community to engage in congregational prayers and get to their places of work on time.”[73]

Effects

[edit]

Main article: Analysis of daylight saving time

Effects on electricity consumption

[edit]

Proponents of DST generally argue that it saves energy, promotes outdoor leisure activity in the evening (in summer), and is therefore good for physical and psychological health,[109] reduces traffic accidents, reduces crime or is good for business.[110] Opponents argue the actual energy savings are inconclusive.[111]

Although energy conservation goals still remain under certain conditions,[112] energy usage patterns have greatly changed since then. In a publication from 2025, based on this change in consumption patterns, such as air conditioning systems, additional consumption is expected to occur more frequently during daylight saving time in the future. [113] Electricity use is greatly affected by geography, climate, and economics, so the results of a study conducted in one place may not be relevant to another country or climate.[114] Nevertheless, while overall electricity usage does not decrease, the evening peak demand is flattened, which in turn has a direct impact on generation costs.[113]

A 2017 meta-analysis of 44 studies found that DST leads to electricity savings of 0.3% during the days when DST applies.[115][116] Several studies have suggested that DST increases motor fuel consumption,[114] but a 2008 United States Department of Energy report found no significant increase in motor gasoline consumption due to the 2007 United States extension of DST.[117] An early goal of DST was to reduce evening usage of incandescent lighting, once a primary use of electricity.[118]

Economic effects

[edit]

It has been argued that clock shifts correlate with decreased economic efficiency and that in 2000, the daylight-saving effect implied an estimated one-day loss of $31 billion on US stock exchanges.[119] Others have asserted that the observed results depend on methodology[120] and disputed the findings,[121] though the original authors have refuted points raised by disputers.[122]

Effects on health

[edit]

There are measurable adverse effects of clock-shifts on human health.[123] It has been shown to disrupt human circadian rhythms,[124] negatively affecting human health in the process,[125] and that the yearly DST clock-shifts can increase health risks such as heart attacks[126] and traffic accidents.[127][128]

A 2017 study in the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics estimated that “the transition into DST caused over 30 deaths at a social cost of $275 million annually”, primarily by increasing sleep deprivation.[129]

A correlation between clock shifts and increase in traffic accidents has been observed in North America and the UK but not in Finland or Sweden.[130] Four reports have found that this effect is smaller than the overall reduction in traffic fatalities.[131][132][133][134] According to data shared by Titan Casket, hospitals see a 24% increase in heart attacks[135] and a 6% increase in fatal crashes[136] each year when the time changes. In 2018, the European Parliament, reviewing a possible abolition of DST, approved a more in-depth evaluation examining the disruption of the human body’s circadian rhythms which provided evidence suggesting the existence of an association between DST clock-shifts and a modest increase of occurrence of acute myocardial infarction, especially in the first week after the spring shift.[137] However a Netherlands study found, against the majority of investigations, contrary or minimal effect.[138] Year-round standard time (not year-round DST) is proposed by some to be the preferred option for public health and safety.[139][140][141][142][143] Clock shifts were found to increase the risk of heart attack by 10 percent,[126] and to disrupt sleep and reduce its efficiency.[144] Effects on seasonal adaptation of the circadian rhythm can be severe and last for weeks.[145]

Effects on social relations

[edit]

DST hurts prime-time television broadcast ratings,[146][126] drive-ins and other theaters.[147] Artificial outdoor lighting has a marginal and sometimes even contradictory influence on crime and fear of crime.[148]

Later sunsets from DST are thought to affect behavior; for example, increasing participation in after-school sports programs or outdoor afternoon sports such as golf, and attendance at professional sporting events.[149] Advocates of daylight saving time argue that having more hours of daylight between the end of a typical workday and evening induces people to consume other goods and services.[150][110][151]

In 2022, a publication of three replicating studies of individuals, between individuals, and transecting societies, demonstrated that sleep loss affects the human motivation to help others, which in its fMRI findings is “associated with deactivation of key nodes within the social cognition brain network that facilitates prosociality.” Furthermore, they detected, through analysis of over three million real-world charitable donations, that the loss of sleep inflicted by the transition to daylight saving time reduces altruistic giving compared to controls (being states not implementing DST). They conclude that the effects on civil society are “non-trivial”.[152]

Another study, which also examined sleep manipulation due to the shift to daylight saving time in the spring, analyzed archival data from judicial punishment imposed by US federal courts which showed sleep-deprived judges exact more severe penalties.[153]

Inconvenience

[edit]

DST’s clock shifts have the disadvantage of complexity. People must remember to change their clocks; this can be time-consuming, particularly for mechanical clocks that cannot be moved backward safely.[154] People who work across time zone boundaries need to keep track of multiple DST rules, as not all locations observe DST or observe it the same way. The length of the calendar day becomes variable; it is no longer always 24 hours. Disruption to meetings, travel, broadcasts, billing systems, and records management is common, and can be expensive.[155] During an autumn transition from 02:00 to 01:00, a clock shows local times from 01:00:00 through 01:59:59 twice, possibly leading to confusion.[156]

Many farmers oppose DST, particularly dairy farmers as the milking patterns of their cows do not change with the time,[126][157][158] and others whose hours are set by the sun.[159] There is concern for schoolchildren who are out in the darkness during the morning due to late sunrises.[126]

Remediation

[edit]

Some clock-shift problems could be avoided by adjusting clocks continuously[160] or at least more gradually[161]—for example, Willett at first suggested weekly 20-minute transitions—but this would add complexity and has never been implemented. DST inherits and can magnify the disadvantages of standard time. For example, when reading a sundial, one must compensate for it along with time zone and natural discrepancies.[162] Also, sun-exposure guidelines such as avoiding the sun within two hours of noon become less accurate when DST is in effect.[163]

Terminology

[edit]

As explained by Richard Meade in the English Journal of the (American) National Council of Teachers of English, the form daylight savings time (with an “s”) was already much more common than the older form daylight saving time in American English (“the change has been virtually accomplished”) in 1978. Nevertheless, dictionaries such as Merriam-Webster’s, American Heritage, and Oxford, which typically describe actual usage instead of prescribing outdated usage (and therefore also list the newer form), still list the older form first. This is because the older form is still very common in print and is preferred by many editors. (“Although daylight saving time is considered correct, daylight savings time (with an “s”) is commonly used.”)[164] The first two words are sometimes hyphenated (daylight-saving(s) time). Merriam-Webster’s also lists the forms daylight saving, daylight savings (both without “time”), and daylight time.[165] The Oxford Dictionary of American Usage and Style explains the development and current situation as follows:

Although the singular form daylight saving time is the original one, dating from the early 20th century—and is preferred by some usage critics—the plural form is now extremely common in AmE. […] The rise of daylight savings time appears to have resulted from the avoidance of a miscue: when saving is used, readers might puzzle momentarily over whether saving is a gerund (the saving of daylight) or a participle (the time for saving). […] Using savings as the adjective—as in savings account or savings bond—makes perfect sense. More than that, it ought to be accepted as the better form.[166]

In Britain, Willett’s 1907 proposal[36] used the term daylight saving, but by 1911, the term summer time replaced daylight saving time in draft legislation.[108] The same or similar expressions are used in many other languages: Sommerzeit in German, zomertijd in Dutch, kesäaika in Finnish, horario de verano or hora de verano in Spanish, and heure d’été in French.[79]

The name of local time typically changes when DST is observed. American English replaces standard with daylight: for example, Pacific Standard Time (PST) becomes Pacific Daylight Time (PDT). In the United Kingdom, the standard term for UK time when advanced by one hour is British Summer Time (BST), and British English typically inserts summer into other time zone names, e.g. Central European Time (CET) becomes Central European Summer Time (CEST).

In North American English, people use the mnemonic “spring forward, fall back” (also “spring ahead …”, “spring up …”, and “… fall behind”) to remember the direction in which to shift the clocks.[167][68]

Computing

[edit]

Changes to DST rules cause problems in existing computer installations. For example, the 2007 change to DST rules in North America required that many computer systems be upgraded, with the greatest onus on e-mail and calendar programs. The upgrades required a significant effort by corporate information technologists.[168]

Some applications standardize on UTC to avoid problems with clock shifts and time zone differences.[169] Likewise, most modern operating systems internally handle and store all times as UTC and only convert to local time for display.[170][171] However, even if UTC is used internally, the systems still require external leap second updates and time zone information to correctly calculate local time as needed. Many systems in use today base their date/time calculations from data derived from the tz database also known as zoneinfo.

IANA time zone database

[edit]

The tz database maps a name to the named location’s historical and predicted clock shifts. This database is used by many computer software systems, including most Unix-like operating systems, Java, and the Oracle RDBMS;[172] HP‘s “tztab” database is similar but incompatible.[173] When temporal authorities change DST rules, zoneinfo updates are installed as part of ordinary system maintenance. In Unix-like systems the TZ environment variable specifies the location name, as in TZ=':America/New_York'. In many of those systems there is also a system-wide setting that is applied if the TZ environment variable is not set: this setting is controlled by the contents of the /etc/localtime file, which is usually a symbolic link or hard link to one of the zoneinfo files. Internal time is stored in time-zone-independent Unix time; the TZ is used by each of potentially many simultaneous users and processes to independently localize time display.

Older or stripped-down systems may support only the TZ values required by POSIX, which specify at most one start and end rule explicitly in the value. For example, TZ='EST5EDT,M3.2.0/02:00,M11.1.0/02:00' specifies time for the eastern United States starting in 2007. Such a TZ value must be changed whenever DST rules change, and the new value applies to all years, mishandling some older timestamps.[174]

Opposition to clock changes

[edit]

See also: Permanent time observation in the United States, Decree time in Russia, Summer time in Europe § Future, Daylight saving time in Asia § Asian countries not using DST, and Daylight saving time in Brazil

A move to permanent daylight saving time (staying on summer hours all year with no clock shifts) is sometimes advocated and is currently implemented in some jurisdictions such as Argentina, Belarus,[175] Iceland, Kyrgyzstan, Morocco,[55] Namibia, Northern Cyprus, Saskatchewan, Singapore, Syria, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Yukon. Although Saskatchewan follows Central Standard Time, its capital city Regina experiences solar noon close to 13:00, in effect putting the city on permanent daylight time. Similarly, Yukon is classified as being in the Mountain Time Zone, though in effect it observes permanent Pacific Daylight Time to align with the Pacific time zone in summer, but local solar noon in the capital Whitehorse occurs nearer to 14:00, in effect putting Whitehorse on “double daylight time”.[citation needed]

The United Kingdom and Ireland put clocks forward by an extra hour during World War II and experimented with year-round summer time between 1968 and 1971.[176] Russia switched to permanent DST from 2011 to 2014, but the move proved unpopular because of the extremely late winter sunrises; in 2014, Russia switched permanently back to standard time.[177] However, the change to permanent DST has proven popular in Turkey, with the Minister of Energy and Natural Resources saying the practice saves “millions in energy costs and reduces depression and anxiety levels associated with short exposure to daylight”.[178]

In September 2018, the European Commission proposed to end seasonal clock changes as of 2019.[179] Member states would have the option of observing either daylight saving time all year round or standard time all year round. In March 2019, the European Parliament approved the commission’s proposal, while deferring implementation from 2019 until 2021.[180] In response to this proposition, the European Sleep Research Society stated “installing permanent Central European Time (CET, standard time or ‘wintertime’) is the best option for public health.”[181] As of October 2020, the decision has not been confirmed by the Council of the European Union.[182] The council has asked the commission to produce a detailed assessment of its effects, but the Commission considers that the onus is on the Member States to find a common position in Council.[183] As a result, progress on the issue is effectively blocked.[184]

In the United States, several states have enacted legislation to implement permanent DST, but the bills would require Congress to change federal law in order to take effect. The Uniform Time Act of 1966 permits states to opt out of DST and observe permanent standard time, but it does not permit permanent DST.[101][185] Florida senator Marco Rubio in particular has promoted changing the federal law to implement permanent DST,[186] with the support of the Florida Chamber of Commerce seeking to boost evening revenue.[187] In 2022, Rubio’s “Sunshine Protection Act” passed the United States Senate without committee review by way of voice consent, with many senators afterward stating they were unaware of the vote or its topic.[188] The bill was stopped in the US House, where questions were raised as to whether permanent DST or standard time would be more beneficial.[103][189] Polling as of 2025 shows a majority of Americans polled now prefer to permanently end DST, with 54% of Americans reporting that a permanent switch to standard time would be preferrable. The emergent majority indicates that permanent DST would also be preferred over no change, with the least popular activity being the changing of the time twice per year regardless of DST or standard time being the permanent method of keeping time.[1][190]

Advocates cite the same advantages as normal DST without the problems associated with the twice-yearly clock shifts. Additional benefits have also been cited, including safer roadways, boosting the tourism industry, and energy savings. Detractors cite the relatively late sunrises, particularly in winter, that year-round DST entails.[191]

Some experts in circadian rhythms and sleep health recommend year-round standard time as the preferred option for public health and safety.[139][140][141][142] However, some experts state that permanent daylight saving time is still a better option when compared to annual clock changes.[192][193] Several chronobiology societies have published position papers against adopting DST permanently. A paper by the Society for Research on Biological Rhythms states: “based on comparisons of large populations living in DST or ST or on western versus eastern edges of time zones, the advantages of permanent ST outweigh switching to DST annually or permanently.”[194] The World Federation of Societies for Chronobiology recommended “reassigning countries and regions to their actual sun-clock based time zones” and held the position of being “against the switching between DST and Standard Time and even more so against adopting DST permanently.”[195] The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) holds the position that “seasonal time changes should be abolished in favor of a fixed, national, year-round standard time,”[196] and that “standard time is a better option than daylight saving time for our health, mood and well-being.”[197] Their position was endorsed by 20 other organizations, including the American College of Chest Physicians, National Safety Council, and National PTA.[198]

Surveys reported between 2021 and 2022 by the National Sleep Foundation, YouGov, CBS, and Monmouth University indicate more Americans would prefer permanent DST.[199][200][201] A 2019 survey by the National Opinion Research Center and a 2021 survey by the Associated Press indicate more Americans would prefer permanent Standard Time.[202][203] The National Sleep Foundation, YouGov, and Monmouth University polls leaned significantly in favor of seeing daylight saving time made permanent. The Monmouth University poll reported 44% preferring year-round DST and 13% preferring year-round standard time.[200] The NORC at the University of Chicago found 79% of those interviewed to be in favor of permanent DST during the Oil Crisis in December 1973; 42% of poll takers supported it the following February.[204]